Social injustice burst open in 2020 around the world. The inequalities and wounds continue to occur and remain raw. Part of the healing process will be social justice, diversity, continued discussions, policy review, and discourse. Spokane is one of the cities working to continue discourse in active ways. An essential step in this is to remember those who have served our Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. One such servant leader in Spokane was Carl Maxey, a distinguished lawyer and civil rights activist.

Long before Maxey became a Gonzaga Law School student, he had a fiery passion for civil rights. Born of a 13-year-old in 1923, he was adopted by the Maxey’s of Spokane. When his adoptive mother became a single mother with no income in 1933, he became a state ward. In 1936, the Spokane Children’s Home board voted children of color would no longer be cared for, and he became a ward of Spokane County. Maxey felt the pain of this event more than any other, and it fueled his fire to fight for a better world.

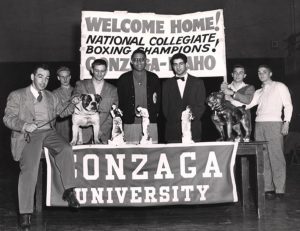

Maxey’s fire helped him grow into a scholar and athlete of nearly all sports. During World War II, Maxey joined the Army as a medic, then studied in Oregon, where he ran track. Unable to join the football team at Eastern or Gonzaga, nor the basketball team at Gonzaga, Maxey joined Gonzaga’s boxing team. He would be undefeated for his entire four years at Gonzaga and notably became the 1950 NCAA light heavyweight boxing national champion. He hung up his gloves and stepped into a new ring after graduation.

Graduating as the first Black person from Gonzaga Law School in 1951, Maxey was also the first Black to start a Spokane legal practice. He soon had a reputation for defending (and winning) legal battles for BIPOC, those less privileged, and breaking through barriers, including segregation issues. Part of his one-two punch was suing high-profile organizations for limiting the growth of community members like Eugene Breckenridge, who Maxey helped to become the first long-term Black teacher in Spokane Public Schools by merely threatening a lawsuit.

While there are countless cases in Maxey’s decades of legal work, several stand out as making a difference. A benchmark case in Spokane is known as the “Haircut Uproar” from 1963. One day a Gonzaga exchange student from Liberia was refused a haircut and kicked out of the white-owned shop, a common segregation in Spokane at the time. After filing an official complaint at the Washington State Board Against Discrimination, the local barber protest became national news alongside other realities of protests across the nation. The Board ruled the owner must not refuse service because of someone’s race, which the Superior Court upheld. This led to the owner closing his shop, and other barbershops stopped refusing service, which provided Maxey’s win a compelling resolution.

Working tirelessly in the 70s, Maxey fought for Spokane’s Blacks’ rights to join social clubs, obtain professional jobs, and buy a house in any Spokane neighborhood. In 1963 and for the remainder of his legal career, Maxey was appointed to the Washington State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission by five presidents. In 1964 Maxey joined Stokely Carmichael and Martin Luther King Jr in the Freedom Summer.

In the 80s, Maxey was a highly sought divorce lawyer though he continued to fight for civil rights, providing pro bono work for 20 percent of cases. As you can see, Maxey led the way, actively changed the accepted norms while invoking changes in the law, and broke barriers for BIPOC of the future. Carl Maxey’s legacy continues today in several ways, including:

- Carl Maxey Center in East Central Spokane — This 501(c)(3) organization was formed in 2017 and is committed to changing lives and improving the well-being of Spokane’s African American community.

- Maxey Law Offices — Started by their father in 1980, Bill and Bevan joined him in 1975 and 1983 respectively. Recently, in 2017 and 2020, Maxey’s grandsons Morgan and Mason also joined the firm which continues the mission, “Integrity, Equality, and Justice.”

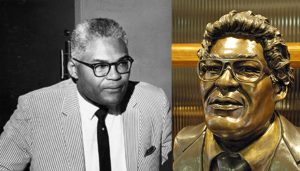

- Carl Maxey bust in the walkway of the Gonzaga Law Library — A bronze bust greets law students from their first day on campus, reminding them if you work hard you can make a difference.

- Carl Maxey Social Justice Scholarship Program at Gonzaga Law School — Announced this January, this scholarship is linked with social justice service requirements. The first recipient(s) will be announced in April.

To learn more about Carl Maxey’s incredible life, some additional resources include the 2008 biography by Jim Kershner “Carl Maxey: A Fighting Life” and the hour-long KSPS documentary on YouTube based on the biography.