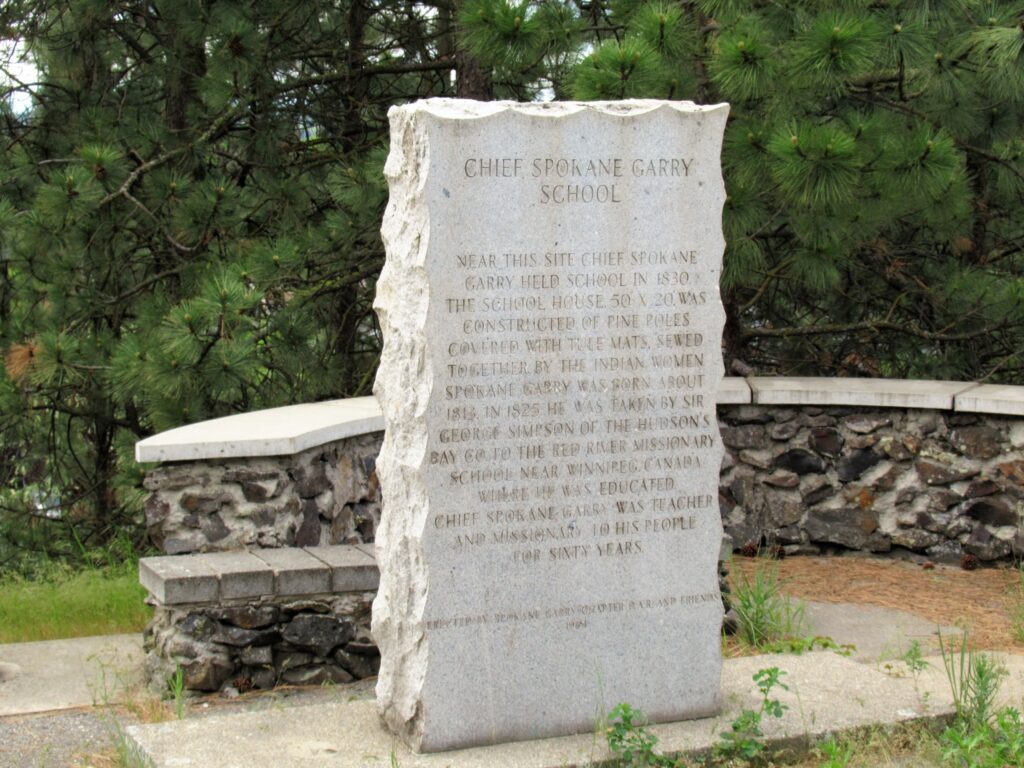

Once upon a time, a statue sat in Spokane’s Chief Garry Park. For some time, this local landmark paid tribute to Native American Chief Spokane Garry, a leader, peacemaker, and educator who had a monumental career as a liaison between early white settlers to Spokane and Native American Tribes in the area. Through the years, the monument became beaten down by age and endured tremendous hardships, ultimately resulting in the statue being torn down in 2008 due to the damage from the elements and acts of vandalism.

Sadly, the life of the monument in this story depicts an eerily similar life lived by the remarkable man the statue depicts.

Spokane Garry’s Early Life

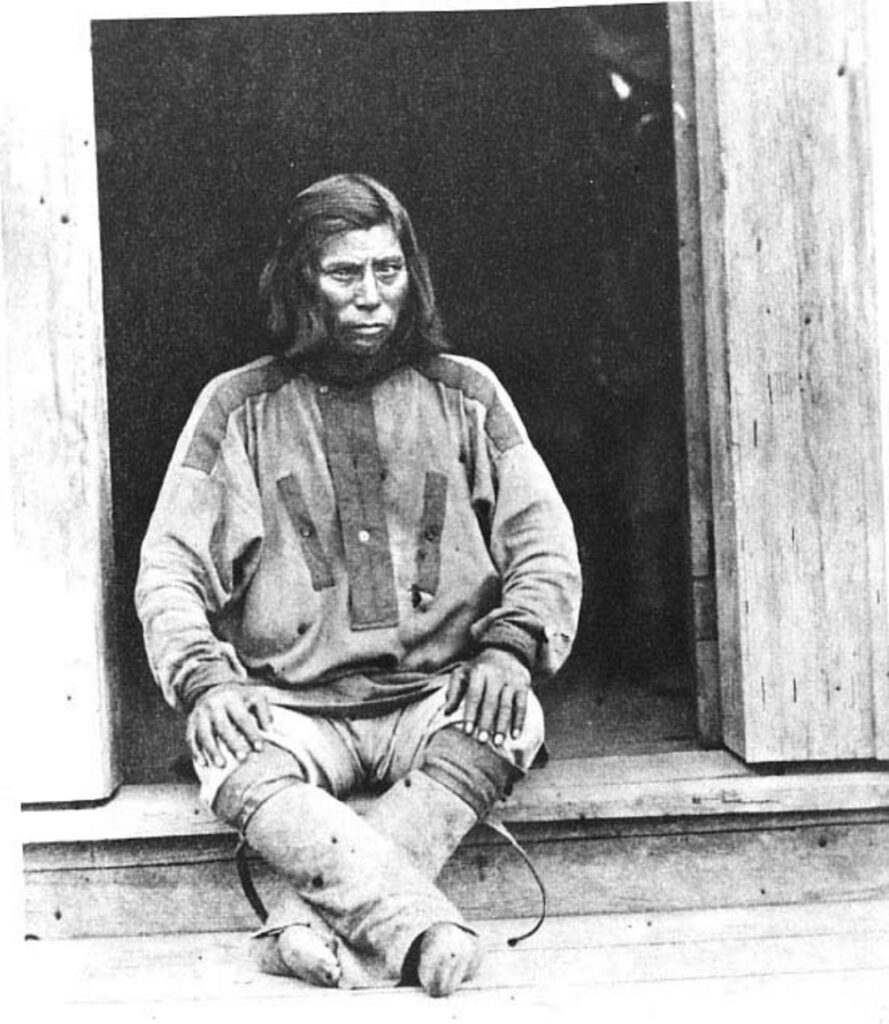

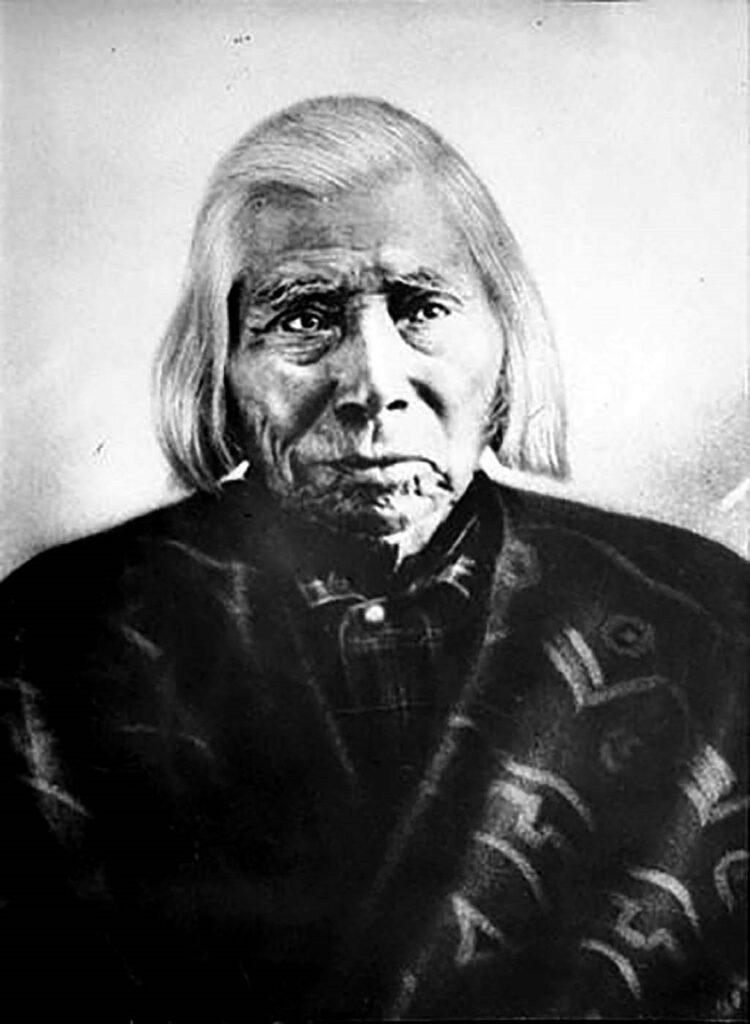

Born in 1811, he was the son of Chief Illum Spokanee, sometimes spelled Illim or Illeeum, who was the chief of the Spokane Tribe. Though most history books will refer to him as Spokane Garry, he was actually born Slough-Keetcha, his original Spokane Salish name. His English name Garry was acquired under a remarkable set of circumstances when he was about 14 years of age that would ultimately set him on a course to become the extraordinary man with a harrowing story we know today.

It all started in 1825 when George Simpson, governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, called a meeting with the Tribal Chiefs, one in which he hoped to discuss his plan to send some young, Native American boys to the Red River Settlement’s Anglican missionary school. His goal was to teach the boys the ways of Christianity and western civilization in the hopes that they would educate the elders of the Tribes with their new teachings.

Chief Illum was one of the eight chiefs at the meeting. Both he and the Kootenai Chief surprised Simpson when they each offered to send one of their own children. Hudson’s Bay employee Alexander Ross later wrote that one of the chiefs stood up and said, “You see, we have given you our children, not our servants, or our slaves, but our own. We have given you our hearts – our children are our hearts – but bring them back to us before they become white men.”

Days later, the boys were baptized and given new names representing their Tribes and the Hudson’s Bay company. The son of the Kootenai Chief was renamed Kootenai Pelly, the name Pelly coming from a Hudson’s Bay governor. Chief Illum’s would go down in history as Spokane Garry, named after Nicholas Garry, a director within the company.

After making the strenuous journey across the Canadian Rockies, surviving the cold, floods, and homesickness, they arrived at the settlement. Here, they would learn English and French, as well as math, agriculture, and Christianity.

For Chief Illum, it would be the last time he saw his son, passing away in 1829. Garry would not return to Spokane and his Tribe for good until 1830 at about 19 years of age. Sadly, Pelly became ill and died at Red River that year.

Garry Returns to Spokane

Upon his return, he quickly became influential among the Middle and Upper Bands of the Spokane Tribe as an important leader and thanks to his newfound languages, he was appointed the title of Tribe’s spokesman in almost all dealings with whites.

Garry worked hard to spread all that he had learned throughout the Tribe. The Spokane Tribe gained a reputation for being agriculturally advanced once he taught them the farming methods he had learned. Some historians even consider Garry to be the “first schoolteacher” in Spokane country, as he built a rough schoolhouse where he taught as many lessons. He even attempted to be an Anglican missionary to his people, teaching them lessons from his very own Bible.

Unfortunately, his teachings seemed inadequate to Governor Simpson upon his return to Spokane in 1841. When he arrived and saw a group of Native Americans gambling with cards, he immediately blamed Garry, claiming that he had forsaken his education and reverted back to what he considered “barbarism.”

Tensions further arose in 1855 as more settlers encroached on the region. Tribes to the south and west of Spokane were beginning to clash with these settlers and miners. An alarmed Governor Stevens, desperate to make peace, set out on a “treaty tour” to encourage Tribes to move reservations. Eventually, he called a meeting of tribal leaders to Spokane, of which Garry was present, and the things he had to say particularly alarmed Garry.

Stevens proposed that the tribes sell their land and more to a reservation shared with the Nez Perce or Yakima Tribes. This scant proposal completely disregarded the cultural differences between each unique, individual Tribe.

The meeting ended with Garry emerging as the spokesman for the gathered Tribes as he was deeply appalled by the proposal and first to speak up, composing an eloquent plea to the settlers for simple respect and human understanding as the tribes were attached to their homelands.

Stevens swore the idea was merely a suggestion and not a demand. Yet over the next few years, the situation rapidly deteriorated. Garry worked hard to keep the young Spokane warriors out of the conflict, but in 1858 things would fall apart once Col. E.J. Steptoe and his troops crossed the Snake River. Garry and another chief intercepted the soldiers as they arrived in the territory. Steptoe explained that they were out on a peaceful expedition but heeded Garry’s request for the troops to withdraw due to the rising tensions. However, before they could, warriors from the Yakima, Palouse, and Coeur d’Alene tribes attacked, along with some of the young Spokane warriors Garry had tried to deter.

Serious repercussions followed, both for the Tribes and Spokane Garry. The federal government was now determined to crush what they considered troublesome tribes. Meanwhile, Garry lost his stature within the Tribe, first for not being able to prevent the attack and second for refusing to join the warriors once the fight broke out.

Killing of the Horses

Garry was heartbroken over the situation, eventually pouring his heart and anger into a letter sent to Governor Stevens and new commander General Newman S. Clark, yet peace would not come. Instead, a punitive expedition led to the Battle of Four Lakes and the Battle of Spokane Plains, commanded by Colonel George Wright. It would be days later that the tragic Killing of the Horses, an event that would leave a dark shadow on Spokane’s early history. Between 800 and 900 horses belonging to the Tribes were rounded up and killed on September 10, 1858, in an attempt to make them powerless.

The Tribes were left beaten and devastated. Garry and prominent Spokane Chief Big Star would meet with Colonel Wright a few weeks later to sign a peace treaty, which mirrored that of a surrender more than anything.

Spokane Garry’s Later Life

Still, the war was over. The following 20 years of Garry’s life would be spent in a patient battle and continuing effort to establish a substantial reservation on ancestral lands so that the culture and life of the Tribe may persevere. Garry endured many meetings with government officials regarding possible reservation sites, but nothing would come of them. Garry wouldn’t get to sign a treaty regarding a reservation for the tribe until he was 76 years old. Even then, the treaty was designed so that the Upper and Middle Spokane Tribes would relinquish their rights to the land and send them to the Coeur d’Alene reservation.

Though he signed the treaty, Garry originally had no intention of leaving the land as he had his farm nestled at the foot of a hill just east of the present-day Hillyard area. Yet he was forced to suffer even more indignity when a white settler took his farm in 1888 after he left for a few days to go fishing.

His family was ultimately forced off the property by the interloper. They packed what they could but had to return for a second trip to grab the rest of their belongings. Upon returning for the rest of their things, Garry found that the cabin burned to the ground.

He attempted to take legal action on the matter to court, but no justice was to be found. His family relocated and set up tepees by Latah Creek and tried to make anew, but locals harassed them. His family uprooted again after a time, eventually moving to Indian Canyon, where a white landowner was gracious enough to let them set up camp. It would be here that Spokane Garry would pass away on January 12, 1892.

Though he lived a long life full of hardship and tragedy, through it all, Spokane Garry remained sturdy, a beacon of peace during a chaotic time in the area’s early history. And although we cannot change the past, we can work together toward a better and equal future for all. Spokane has since put its best foot forward to do right by Spokane Garry since his departure from his homeland. Gone but certainly not forgotten, statues and monuments, and even parks and schools have been either named after or created to pay tribute to his legendary tribal chief who simply wanted what we all want — peace.