The year is 1896. While the nation hummed with industrial progress and societal shifts, a different kind of journey was about to unfold in the Pacific Northwest. From the burgeoning city of a then Spokane Falls, Norwegian immigrant Helga Estby stood ready to embark on an audacious endeavor: a walk across the entire country to New York City. The stakes were deeply personal – the survival of her family’s farm – and the reward, a promised $10,000, represented a lifeline against looming foreclosure.

As she continued to venture forward, newspapers would call her trek ‘astonishing.’ Still, the genuine astonishment would await her at the finish line, when a journey meant to defy fate would instead expose the Gilded Age’s gilded promises and lay bare the rules of a game already rigged against mothers, immigrants, and dreamers.

A Hard Life for Helga Estby

Born in 1860 in Christiania, Norway (now Oslo), Helga Avilda Ida Marie Johanssen’s early life was marked by loss and resilience. At just two years old, she lost her father, leaving her mother, Karen, to navigate life as a widow. Karen later remarried a merchant named Haug, whose financial stability allowed Helga to attend private school, where she excelled in English, science, and religion. In 1871, as economic stagnation loomed over Norway, the family emigrated to the United States, settling in Manistee, Michigan. Eleven-year-old Helga quickly adapted to her new surroundings, improving her language skills and immersing herself in the bustling Scandinavian community.

However, life in Manistee was not without challenges; a devastating fire destroyed much of the town shortly after their arrival. Despite this, the community rebuilt, and Helga’s formative years were shaped by the resilience of those around her, as if the universe was already preparing her for her incredible journey. It is believed that Manistee is likely the first place young Helga learned about the women’s suffrage movement, as her new home made tidal waves for change in its strong showing of support for the 1874 Michigan Suffrage Referendum. However, it would still ultimately fail statewide.

At 16, Helga’s life took a dramatic turn when she became pregnant out of wedlock—a situation that carried significant social stigma at the time. Her parents arranged for her to marry Ole Estby, a skilled carpenter and fellow Scandinavian immigrant. The couple wed in October 1876, and their first child, Clara, was born the following month.

Seeking new opportunities, Helga and Ole moved west, eventually homesteading in Yellow Medicine County, Minnesota. Life on the prairie was grueling; the family lived in a sod house with a dirt floor, a stark contrast to the comforts they had known. Despite the hardships, Helga and Ole persevered, raising their growing family and dreaming of a better future.

Tough Times in the Wild West

Another fire that would nearly reach their makeshift prairie home, threats of deadly bacterial infection diphtheria, and a catastrophic storm known as “Black Friday” in June of 1885, which would quickly be followed by another severe storm a month later, would be all the Estbys could endure before packing up and moving on Spokane Falls. The prospering city would prove fruitful for the Estbys as Ole quickly found work and a cozy block east of Division Street.

Still, an unmanageable population surge would have the family relocating once again. In 1892, they purchased 160 acres of farmland just 25 miles southeast of the Lilac City in the town of Mica Creek. Fondly dubbing their modest enclave “Little Norway,” the – now – large family had high hopes for the farm’s prosperity, which was depended upon to feed their eight children.

But the promise of stability was short-lived. By April 1893, the Panic of 1893 swept across the nation, triggering a deep economic depression that devastated families like the Estbys. Banks shuttered, businesses collapsed, and unemployment soared, leaving no government relief in sight. Ole would also experience an untimely back injury that would further compound their struggles as it prevented him from working the farm and instead forced him into borrowing against it.

Despite his efforts, the mounting debt proved impossible to overcome, and by 1896, the Estbys faced the grim reality of a looming foreclosure. As the weight of financial despair grew heavier, Helga realized that conventional solutions would no longer suffice.

These Boots Are Made For Walking 4,000 Miles From Spokane to New York

In May of 1896, Helga would take a gamble of a lifetime, wagering everything on a seven-month walk from Spokane to New York when an anonymous sponsor, said to be affiliated with “eastern parties” and working on a project to promote a new vision of womanhood, contracted to pay her $10,000 should she succeed. Inspired by the travels of journalist Nellie Bly and a staunch supporter of women’s suffrage, Helga believed this 4,000-mile journey would not only save her family’s farm but also demonstrate the strength and capabilities of women.

Though her plan looked good on paper, many were quick to point out its flaws in practice, as Helga had just given birth the year before and was still recovering from a pelvic injury. Members of her own family would call her decision to leave behind her husband with seven of their children irresponsible and improper, as her place was with them.

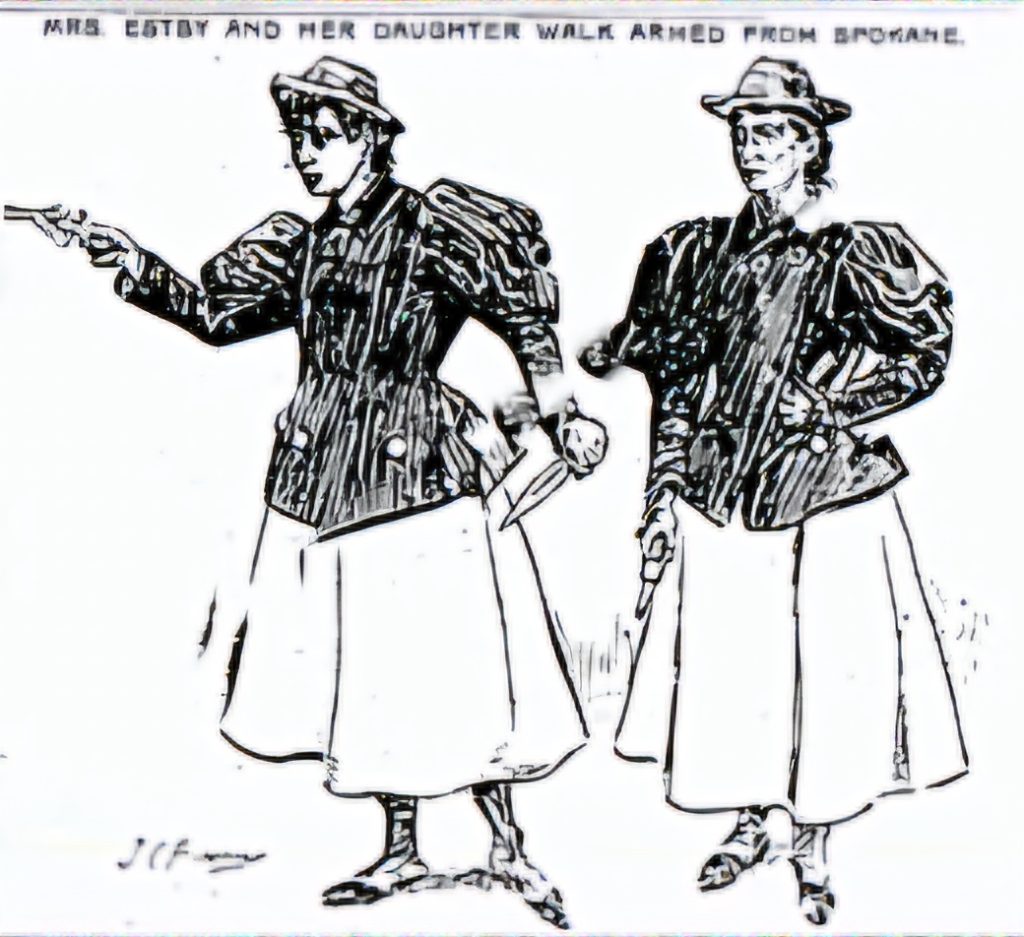

Undeterred by these criticisms and fueled by a fierce determination, Helga convinced her shy but dependable 17-year-old daughter, Clara, to join her. As part of the stipulation in the contract, they were only allowed to start with $5 each and were to pay their expenses by selling their mother-daughter studio portraits, which they sold as souvenirs. As for the rest, they traveled light with only their “necessities,” which included a curling iron for Clara’s hair, a “pepper-gun” filled with cayenne powder, and a Smith-and-Wesson revolver alongside a compass, map, and medical supplies.

Their departure was officially announced on May 5 at the Spokesman Review in Spokane, where they received a letter of introduction from Mayor H.N. Belt, further authenticated by the state treasurer’s signature and seal. The following morning, the mother-daughter duo set off on their ambitious cross-country trek.

The journey proved as dangerous as it was grueling. Helga and Clara walked between 25 and 35 miles each day, following the rail lines to keep from getting lost. Railroad section houses and the kindness of strangers provided respite from the elements, with Helga and Clara often repaying their hosts by cooking, cleaning, and sewing.

Their daily routine included stops at local newspaper offices to share their progress, keeping the nation informed of their remarkable journey. They faced a relentless barrage of natural obstacles: snowstorms that obscured their path, heat waves that threatened to overwhelm them, flash floods that washed out bridges, and mountains that tested their endurance.

Near La Grande, Oregon, Clara’s self-defense against a persistent hobo, which involved shooting him in the leg, became a sensational news story, casting the pair as tough, gun-toting women of the Wild West. Despite the hardships, they pressed on, collecting autographs from awestruck governors, mayors, and political leaders by the time they reached Pennsylvania. It was there, however, that Clara’s sprained ankle introduced a new challenge, forcing Helga to request a crucial extension from their sponsor and casting a shadow of uncertainty over their final push to New York.

A Bitter End to a Hard-Fought Journey

It was Christmas Eve when they finally reached the Manhattan office of the New York World newspaper, with the dynamic duo believing themselves to have arrived just before their deadline. To their utter devastation, the sponsor refused to honor the contract, asserting that they had missed the original agreed-upon deadline of December 13, and that despite having walked 4,600 miles and wearing out 32 pairs of shoes along the way, they had already rejected their request for an extension.

They even went so far as to decline any type of financial support for their trip back home, leaving the women destitute in an unknown place. At the time when all this transpired, it was a common practice for newspapers of that time period to pull various promotional stunts to attract readers, which begs the question of whether the money ever existed at all.

They spent the next few months working to save for a train trip to Spokane. Amid their despair, news from home brought further devastation. Bertha had died of diphtheria, and the remaining children faced quarantine under Ole’s care, leaving the family alone in tragedy. Upon learning of her daughter’s death, Helga made a public appeal for help.

Railroad tycoon Chauncey Depew took it upon himself to provide them tickets to travel to Minneapolis, where Helga’s attempt at damage control was to inform reporters that she and the New York sponsor had arranged a publishing deal for a book based on their journey. Then they would receive their cash prize.

By spring, they finally returned to Mica Creek, only to find Johnny had also died of diphtheria in their absence. The trip, once envisioned as salvation for the family, had become a symbol of loss and estrangement, and they would still lose the family farm just a few years later in 1901.

How a Forgotten Walk Was a Step in the Right Direction

Helga’s return to Mica Creek in 1897 brought little relief, as the journey’s cost had proven far greater than its rewards. Greeted by a grieving family and a Norwegian-American community steeped in resentment, Helga found herself shunned for what many saw as a reckless abandonment of her responsibilities. Though the eventual loss of the farm would seem to underscore the futility of her efforts, the move to Spokane offered the family a chance to begin a new life. Ole’s success in construction brought new financial security and the construction of their very own two-story home, and Helga found purpose with her contributions to Washington’s successful 1910 woman suffrage campaign.

In her later years, she explored painting and began writing memoirs of her journey, attempting to preserve her story despite lingering disapproval from her surviving children. Though her writings were tragically destroyed after she died in 1942, Helga’s story has been revived by descendants and scholars who have reframed her journey as an act of extraordinary determination, with the publication of works such as “Bold Spirit” and “The Daughter’s Walk.”

Despite the initial bitterness and the decades of silence that followed, Helga’s transcontinental walk, once a source of family pain, has gradually emerged as a poignant reminder of history’s complexities. While her contemporaries may have judged her choices harshly, time has offered a broader lens through which to view her audacious undertaking.

Her story now stands as a testament to human resilience, reminding us that even the most challenging journeys—filled with loss, estrangement, and unfulfilled dreams—can leave behind legacies of inspiration. Helga’s walk across America continues to spark dialogue and reflection, offering valuable insights into the sacrifices required to challenge societal norms and the enduring spirit of those who dared to break barriers.